I was sitting in a doctor’s office the other day, reading The Atlantic on my phone since I forgot to bring a book. The article that got my attention was titled The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem by Alex Reisner. He is a computer programmer who has written extensively about generative artificial intelligence, made famous by ChatGPT and now being used in search engines, customer service, and elsewhere. It has rapidly become ubiquitous. For example, if you use Google to look up something, the answer is generated by that company’s version of AI.

I am OK with that. I often use ChatGPT in research, carefully checking the citations and links it provides. I don’t use it to write these pieces. That would be cheating.

What I, and many others, take issue with is how these large language models are being trained. Reisner’s article points out that court documents he obtained indicate that Meta, the company that owns Facebook, pirated millions of books and research papers to train its flagship AI model, Llama 3. It did so by using LibGen, a notorious buccaneer of copyrighted materials. Founded in Russia, it is known as a “shadow library.”

Rather than paying authors to use their work, LibGen steals it. Meta reportedly decided to use LibGen to train Llama 3. Now, it is being sued by several authors, including Sarah Silverman and Junot Diaz, for copyright infringement. Open AI, which owns ChatGPT, is also being sued and accused of copyright infringement by The Authors Guild, The New York Times, and others. So, while I use ChatGPT and accept that AI is going to increasingly be part of the intellectual fabric of society, these companies are making billions of dollars in profit from other people’s work. The creators should be compensated.

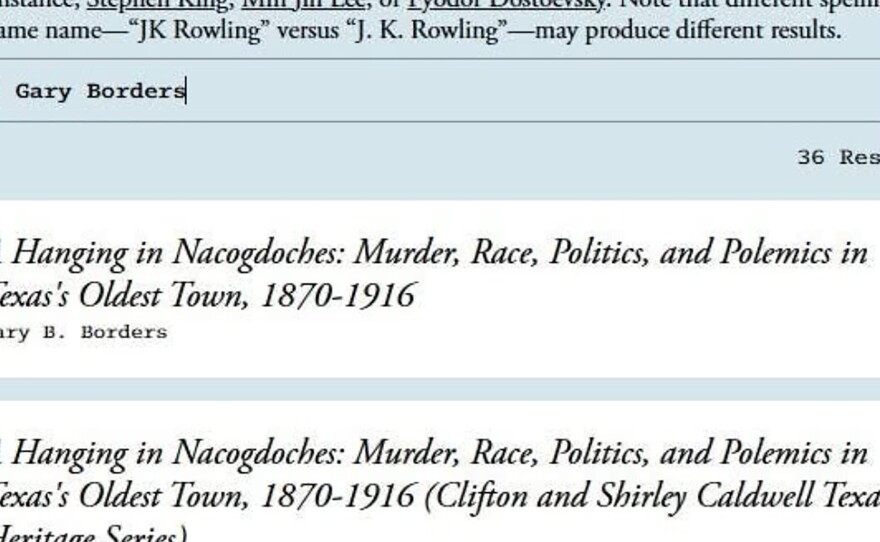

Reisner also provided a search bar in his article so one could search for an author in LibGen, with some caveats. There is no way of knowing what content Meta and Open AI used to train their models. Just because a particular title is in LibGen doesn’t necessarily mean it was used to train one of those AI models.

With that caveat in mind, I typed my name into Reisner’s search bar. A total of 36 results popped up, most having nothing to do with me. But the top two results were a book I wrote that was published 19 years ago by the University of Texas Press: A Hanging in Nacogdoches: Murder, Race, Politics, and Polemics in Texas’s Oldest Town, 1870-1916.

LibGen has stolen my book! Could I be entitled to compensation, as the lawyer commercials say? Doubtful. I don’t even know who to sue. LibGen is pretty shady as to ownership. It constantly changes domains and mirror sites to evade lawsuits from publishers, such as Elsevier, a major academic journal and book publisher.

The Hanging book is still in print, thanks to print-on-demand technology. It sells regularly at a Nacogdoches shop, usually to tourists drawn to the title. It can also be found on Amazon and other book sites.

The Hanging books can also be found in a box in my garage. I buy a box a year wholesale from UT Press to keep the Nacogdoches store stocked, plus occasional requests from someone who wants a signed copy. Every October, UT-Press deposits a royalty payment in my bank account, usually enough to take my wife out for Mexican food.

What the heck. I asked ChatGPT if it uses LibGen. Here is its response:

LibGen is an unauthorized repository of copyrighted content, including books and academic papers, often shared without the permission of publishers or authors. OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, follows strict legal and ethical guidelines and does not use data from illegal or pirated sources like LibGen in training or in generating responses.

OK, then. I guess the courts eventually will have the final say.